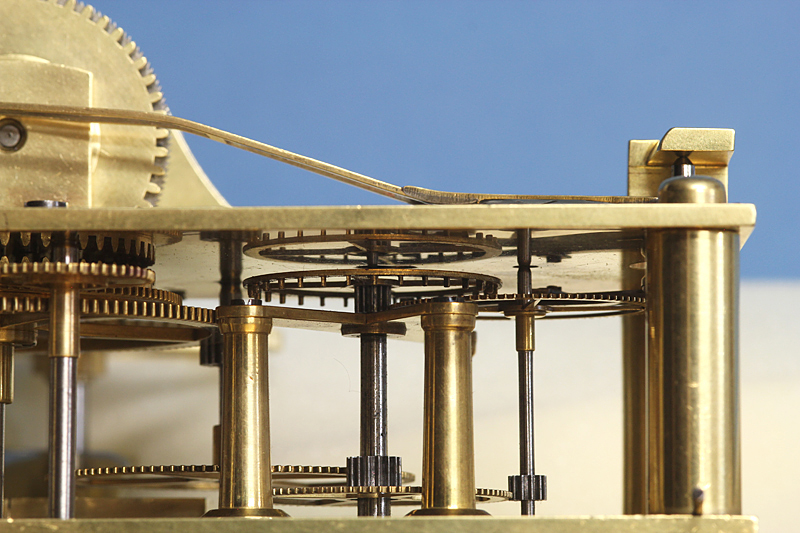

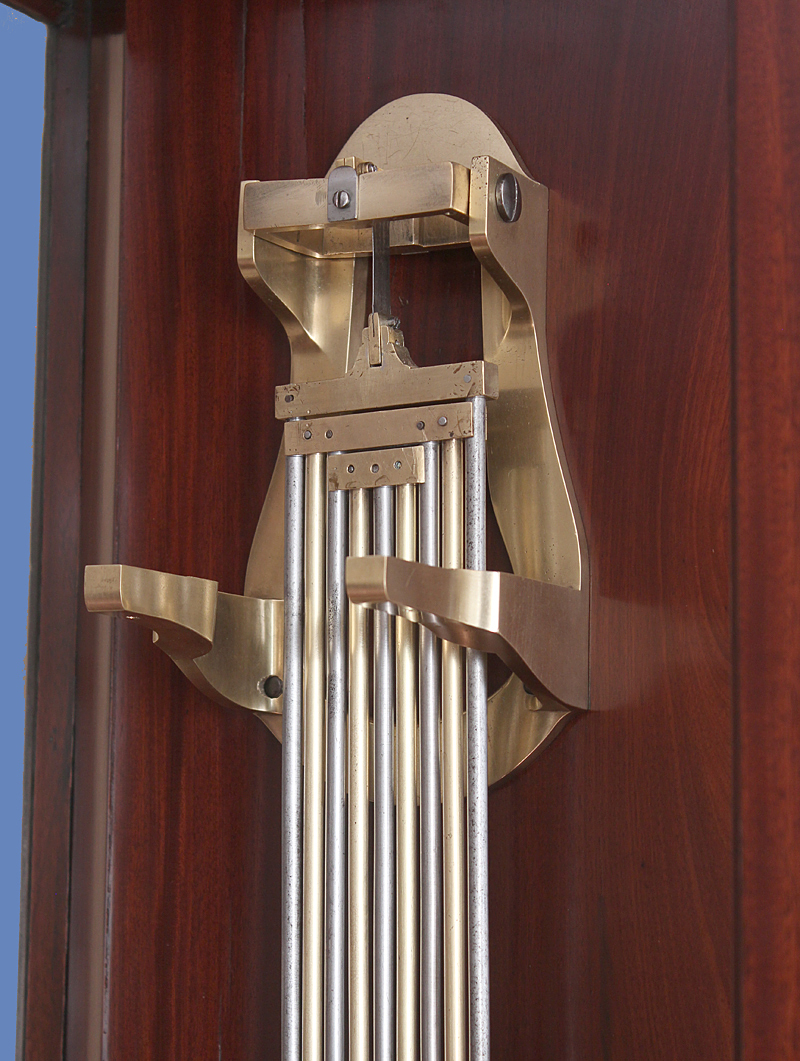

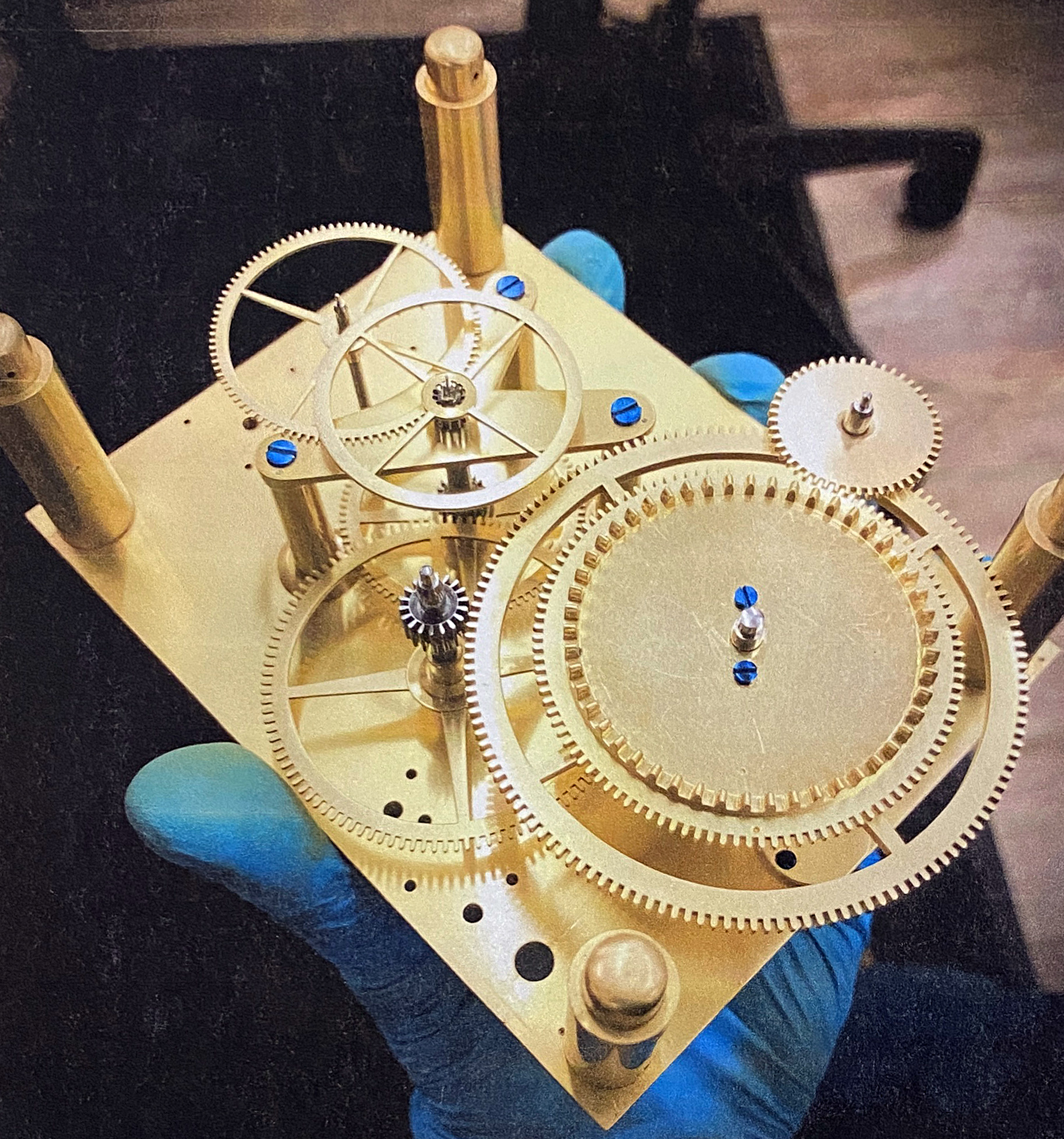

French Floor Standing Thirty-day Regulator with Coteau Dial, Cardinaux, Paris, c. 1807, removable stepped and dental molded cornice above the fully glazed paneled case with raised panel base, 10 1/2-in. dia. brass bezel enclosing the convex glass, polychrome roman numeral dial with arabic five-minute markings, annual calendar with month and date, raised zodiac calendar and symbols on a cobalt blue ground, and signed "Cardinaux a Paris," along with the enameller "Coteau 1807," pierced gilt hands indicating hours, minutes, and solar time, steel hands for sweep center seconds, and date, thirty-day weight-driven movement with a barrel mounted off the backplate, maintaining power, pinwheel escapement with adjustable steel compass-style pallets, and brass ladder-form crutch with screw beat adjustment, nine-rod bimetallic grid-iron pendulum suspended from a shaped brass bracket with gimballed steel spring, weight suspended down the back of the case via a pulley mounted under the removable cornice, ht. 80 1/2 in.

As evidence of the clock’s importance, the dial was realised by Joseph Coteau, who was the most important enamelist of his day. Coteau clock dials have a characteristic style due to their superior quality as to their subject. His most distinct decoration consisted of delicate numerals with small garlands of flowers. Coteau dials are extremely rare; they are sometimes “secretly” inscribed in either pen or brush on the reverse. In addition to their scarcity and supreme quality, his dials and enamel plaques only accompanied the most quality mechanisms. Coteau is known for a technique of relief enamel painting, which he perfected along with Parpette and which was used for certain Sèvres porcelain pieces, as well as for the dials of very fine clocks. Among the pieces that feature this distinctive décor are a covered bowl and tray in the Sèvres Musée national de la Céramique (Inv. SCC2011-4-2); a pair of “cannelés à guirlandes” vases in the Louvre Museum in Paris (see the exhibition catalogue Un défi au goût, 50 ans de création à la manufacture royale de Sèvres (1740-1793), Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1997, p. 108, catalogue n° 61); and the “Comtesse du Nord” tray and bowl in the Pavlovsk Palace in Saint Petersburg (see M. Brunet and T. Préaud, Sèvres, Des origines à nos jours, Office du Livre, Fribourg, 1978, p. 207, fig. 250). A blue Sèvres porcelain lyre clock by Courieult, whose dial is signed “Coteau” and is dated “1785”, is in the Musée national du château in Versailles; it appears to be identical to the example mentioned in the 1787 inventory of Louis XVI’s apartments in Versailles (see Y. Gay and A. Lemaire, “Les pendules lyre”, in Bulletin de l’Association nationale des collectionneurs et amateurs d’Horlogerie ancienne, autumn 1993, n° 68, p. 32C). Coteau supplied dials to Robert Robin and Ferdinand Berthoud, both clockmakers to Louis XVI.

Joseph Coteau, an enameler of clock dials, seems to have taken up jewel enameling in 1779 or 1780 and quickly became known as the most proficient at the art, goth with porcelains and with dials. Optimistically supposing his dials would never be touched except with the greatest care, he refined his technique to an almost unbelievable minuteness; and so it happens that just when movements and cases were being given an unprecedented perfection of finish, an enameler appeared to provide dials worth of them. Indeed, Coteau has remained unequalled; his techniques and motifs were in use throughout the nineteenth century, but although the best of his successors were able to reach his level of virtuosity, they never achieved his perfect proportions nor his luch sweetness, which was an attribut of the ancien regime alone.

True solar time, shown by sundials, fluctuates from day to day due to earth’s tilted rotation axis and its elliptical orbit around the sun, and according to the longitude of the observation point. Timepieces, on the other hand, give mean time, which disregards these differences and divides time into equal hours for every day of the year. Solar time and mean time coincide four times a year: April 15th, June 14th, September 1st and December 24th. The rest of the time, the variation ranges from minus 16 minutes and 23 seconds on November 4th to plus 14 minutes and 22 seconds on February 11th. Although knowing the difference between the two is of no practical significance today, 'equation of time' tables showing the difference between true solar time and mean time were essential for setting clocks in the past and for astronomers to be able to follow cosmic events. Sundial readings or sightings could be converted by referencing these tables; some higher end timepieces (like this one!) and watches display both solar and mean time. more on wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equation_of_time

images and videos of the restoration (including equation of time works) can be seen here: restoration

As evidence of the clock’s importance, the dial was realised by Joseph Coteau, who was the most important enamelist of his day. Coteau clock dials have a characteristic style due to their superior quality as to their subject. His most distinct decoration consisted of delicate numerals with small garlands of flowers. Coteau dials are extremely rare; they are sometimes “secretly” inscribed in either pen or brush on the reverse. In addition to their scarcity and supreme quality, his dials and enamel plaques only accompanied the most quality mechanisms. Coteau is known for a technique of relief enamel painting, which he perfected along with Parpette and which was used for certain Sèvres porcelain pieces, as well as for the dials of very fine clocks. Among the pieces that feature this distinctive décor are a covered bowl and tray in the Sèvres Musée national de la Céramique (Inv. SCC2011-4-2); a pair of “cannelés à guirlandes” vases in the Louvre Museum in Paris (see the exhibition catalogue Un défi au goût, 50 ans de création à la manufacture royale de Sèvres (1740-1793), Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1997, p. 108, catalogue n° 61); and the “Comtesse du Nord” tray and bowl in the Pavlovsk Palace in Saint Petersburg (see M. Brunet and T. Préaud, Sèvres, Des origines à nos jours, Office du Livre, Fribourg, 1978, p. 207, fig. 250). A blue Sèvres porcelain lyre clock by Courieult, whose dial is signed “Coteau” and is dated “1785”, is in the Musée national du château in Versailles; it appears to be identical to the example mentioned in the 1787 inventory of Louis XVI’s apartments in Versailles (see Y. Gay and A. Lemaire, “Les pendules lyre”, in Bulletin de l’Association nationale des collectionneurs et amateurs d’Horlogerie ancienne, autumn 1993, n° 68, p. 32C). Coteau supplied dials to Robert Robin and Ferdinand Berthoud, both clockmakers to Louis XVI.

Joseph Coteau, an enameler of clock dials, seems to have taken up jewel enameling in 1779 or 1780 and quickly became known as the most proficient at the art, goth with porcelains and with dials. Optimistically supposing his dials would never be touched except with the greatest care, he refined his technique to an almost unbelievable minuteness; and so it happens that just when movements and cases were being given an unprecedented perfection of finish, an enameler appeared to provide dials worth of them. Indeed, Coteau has remained unequalled; his techniques and motifs were in use throughout the nineteenth century, but although the best of his successors were able to reach his level of virtuosity, they never achieved his perfect proportions nor his luch sweetness, which was an attribut of the ancien regime alone.

True solar time, shown by sundials, fluctuates from day to day due to earth’s tilted rotation axis and its elliptical orbit around the sun, and according to the longitude of the observation point. Timepieces, on the other hand, give mean time, which disregards these differences and divides time into equal hours for every day of the year. Solar time and mean time coincide four times a year: April 15th, June 14th, September 1st and December 24th. The rest of the time, the variation ranges from minus 16 minutes and 23 seconds on November 4th to plus 14 minutes and 22 seconds on February 11th. Although knowing the difference between the two is of no practical significance today, 'equation of time' tables showing the difference between true solar time and mean time were essential for setting clocks in the past and for astronomers to be able to follow cosmic events. Sundial readings or sightings could be converted by referencing these tables; some higher end timepieces (like this one!) and watches display both solar and mean time. more on wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equation_of_time

images and videos of the restoration (including equation of time works) can be seen here: restoration